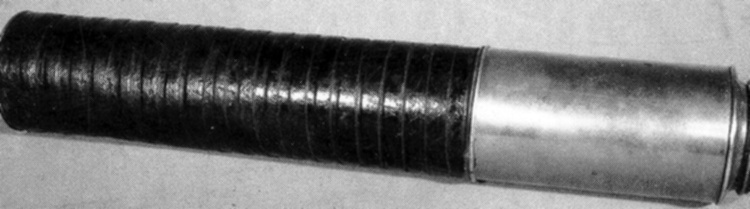

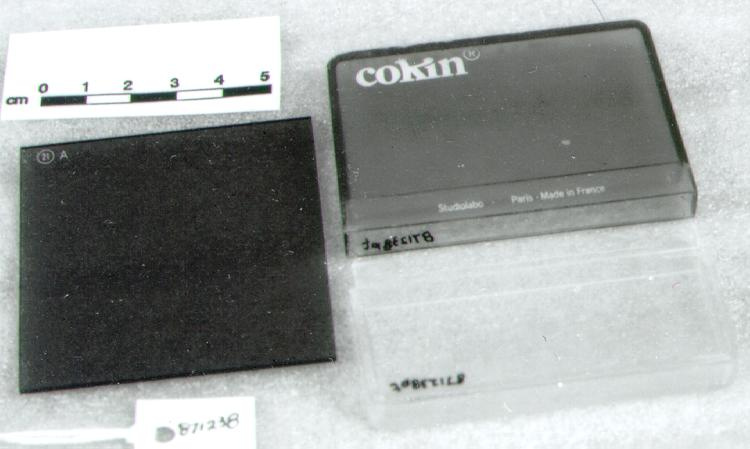

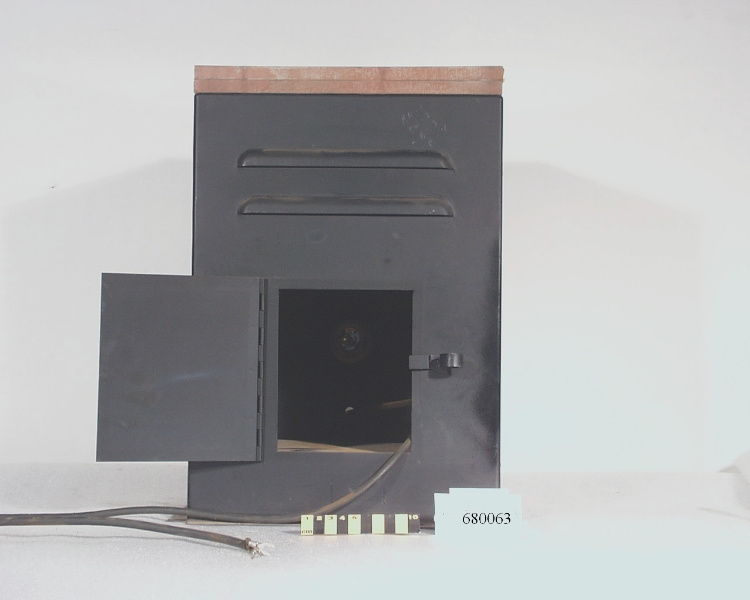

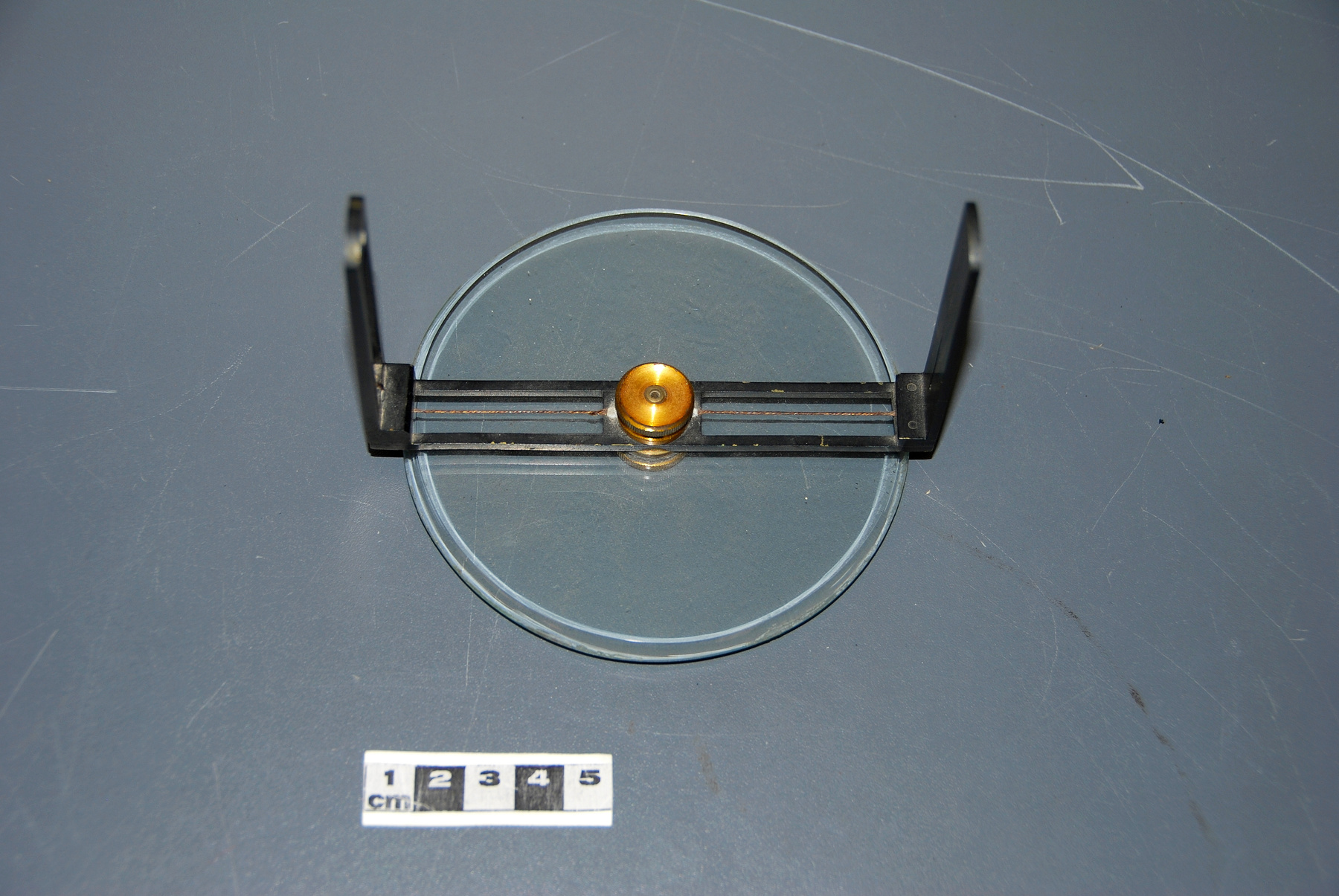

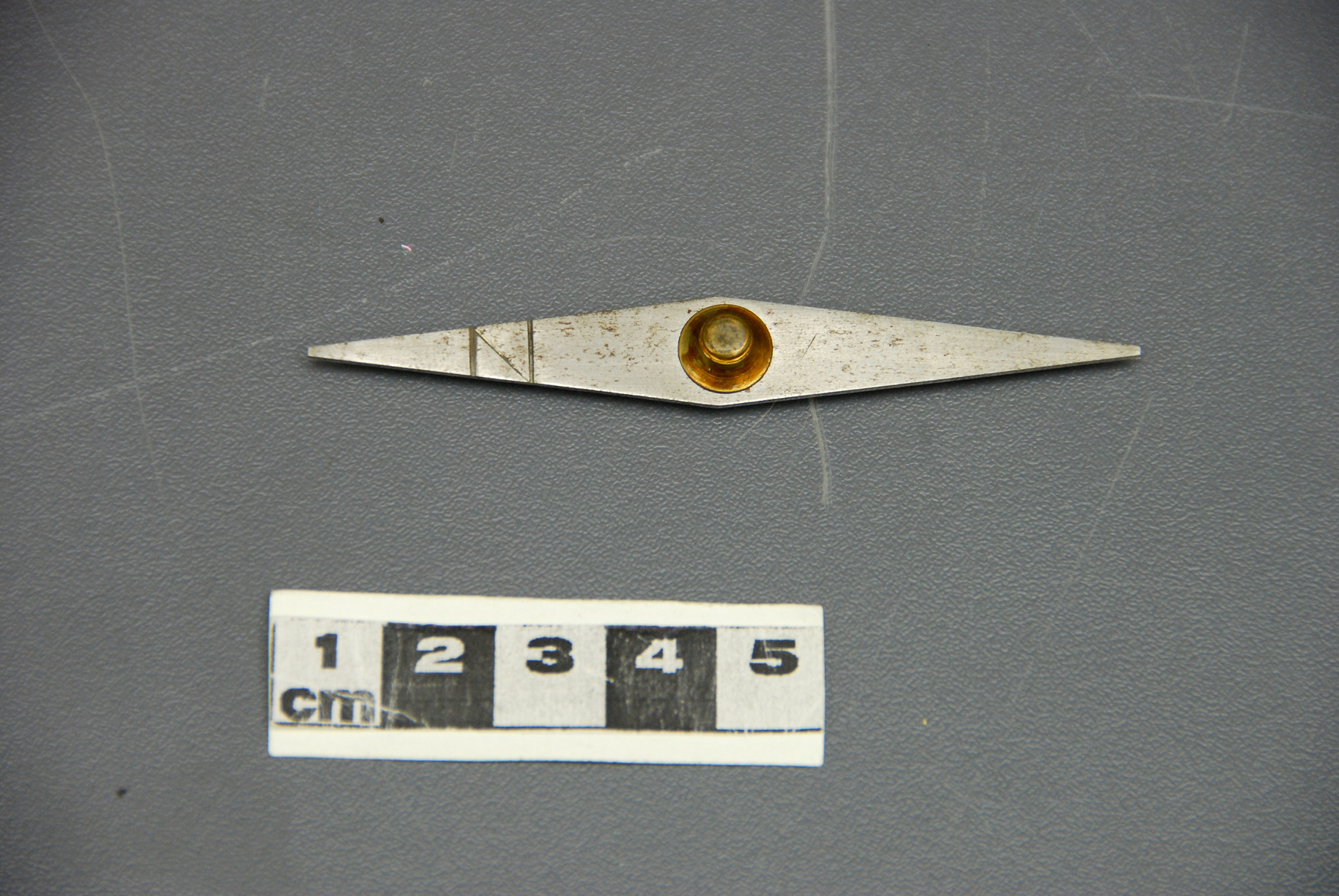

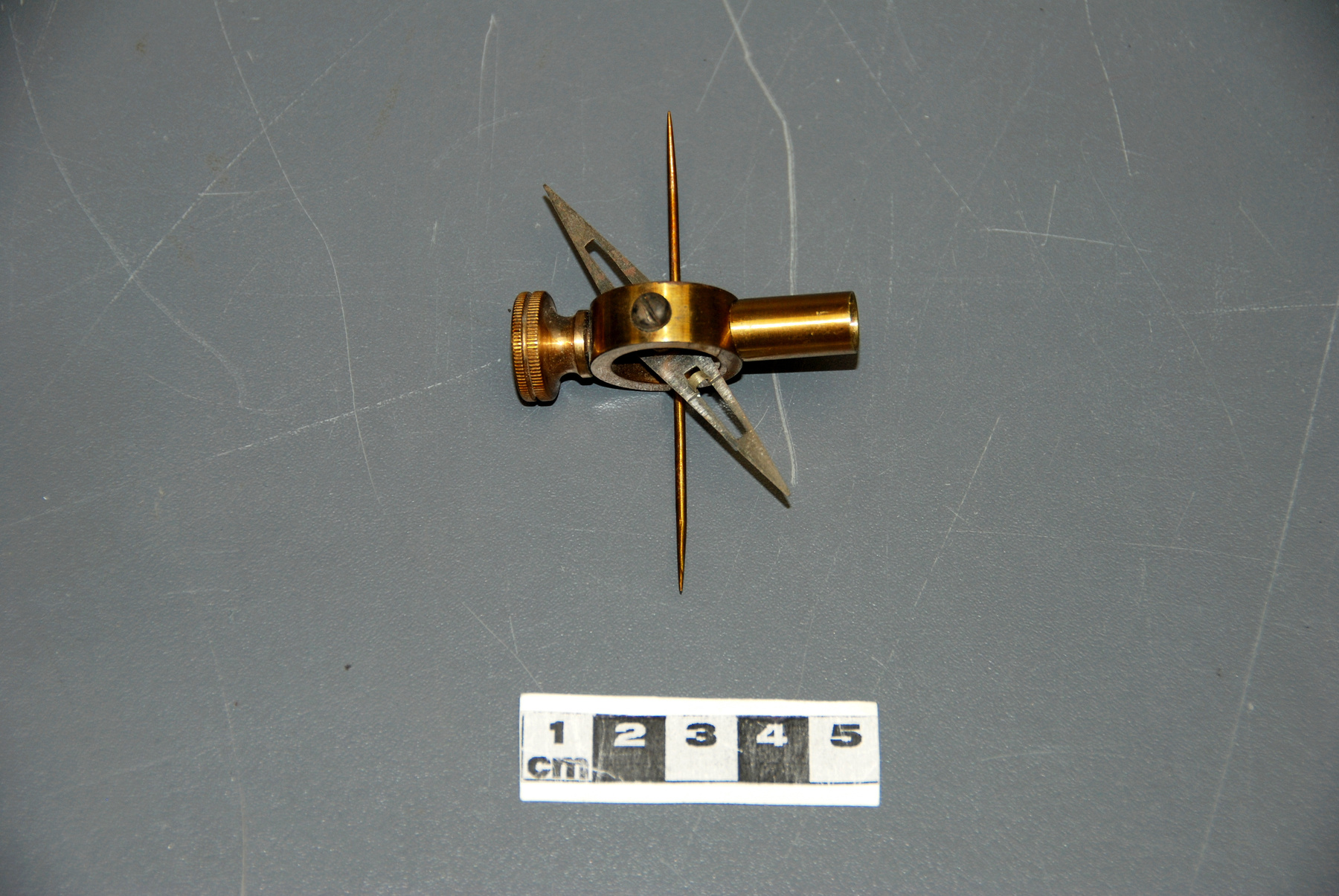

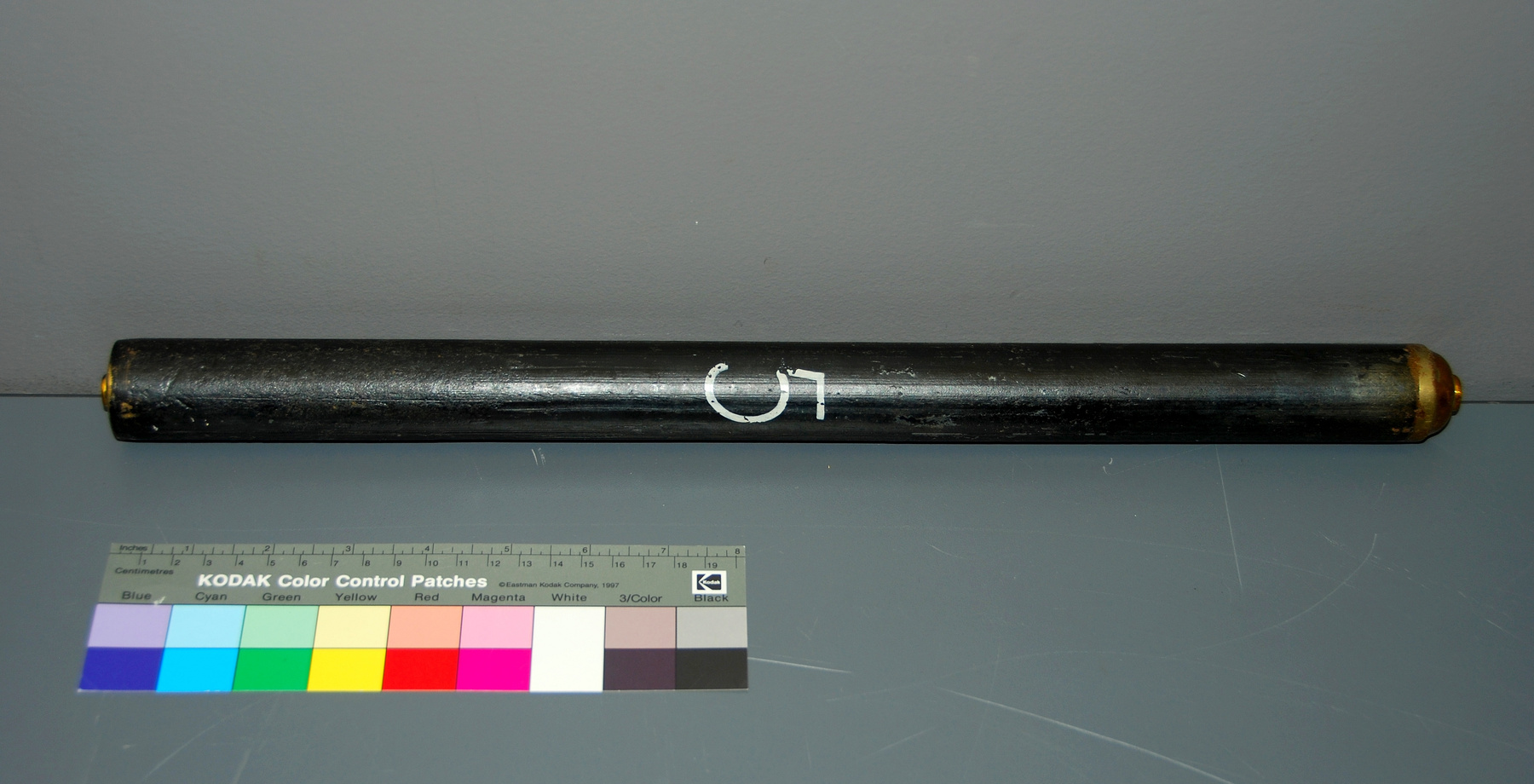

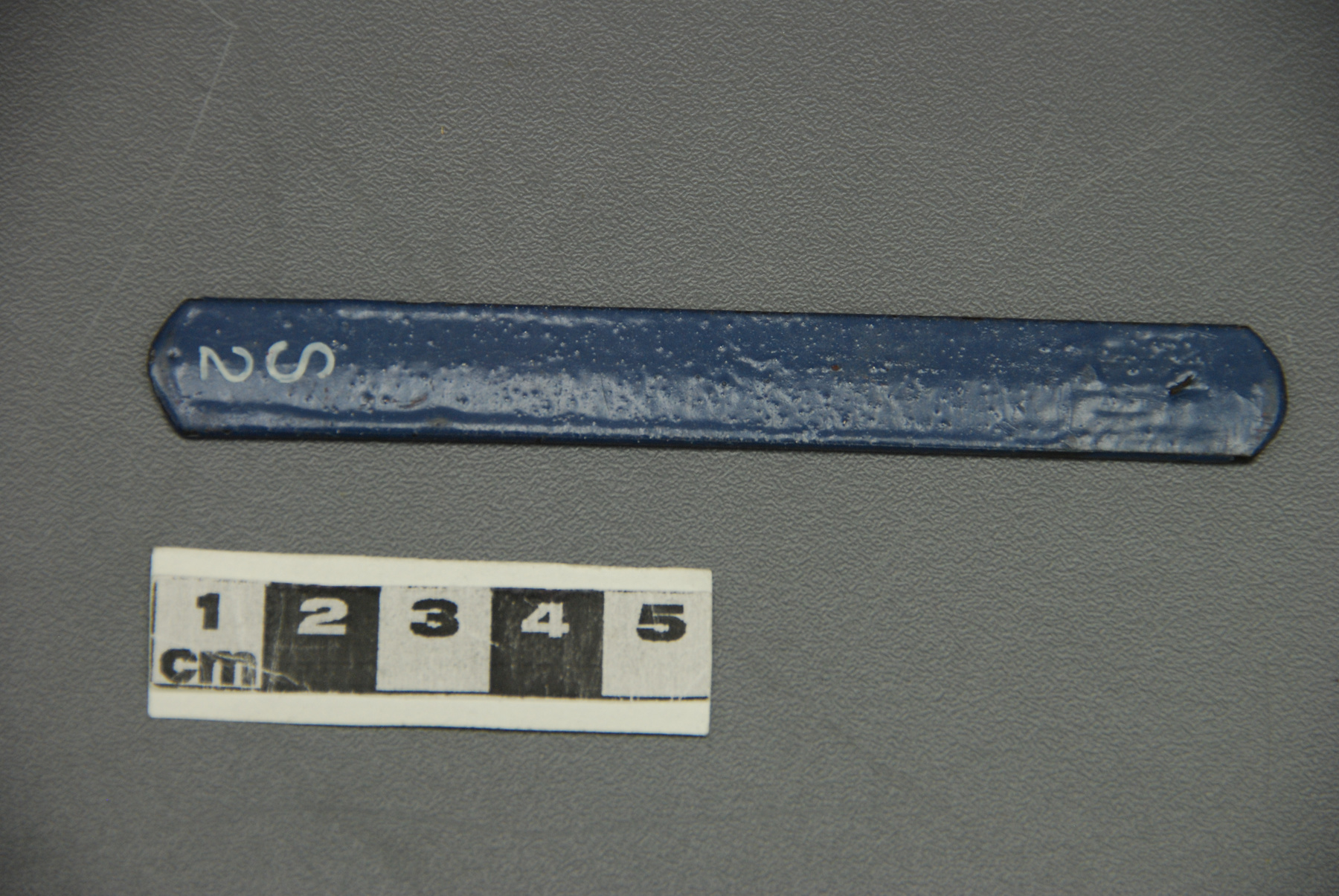

Lentille de phares à signaux

Utiliser cette image

Puis-je réutiliser cette image sans autorisation? Oui

Les images sur le portail de la collection d’Ingenium ont la licence Creative Commons suivante :

Copyright Ingenium / CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

ATTRIBUER CETTE IMAGE

Ingenium,

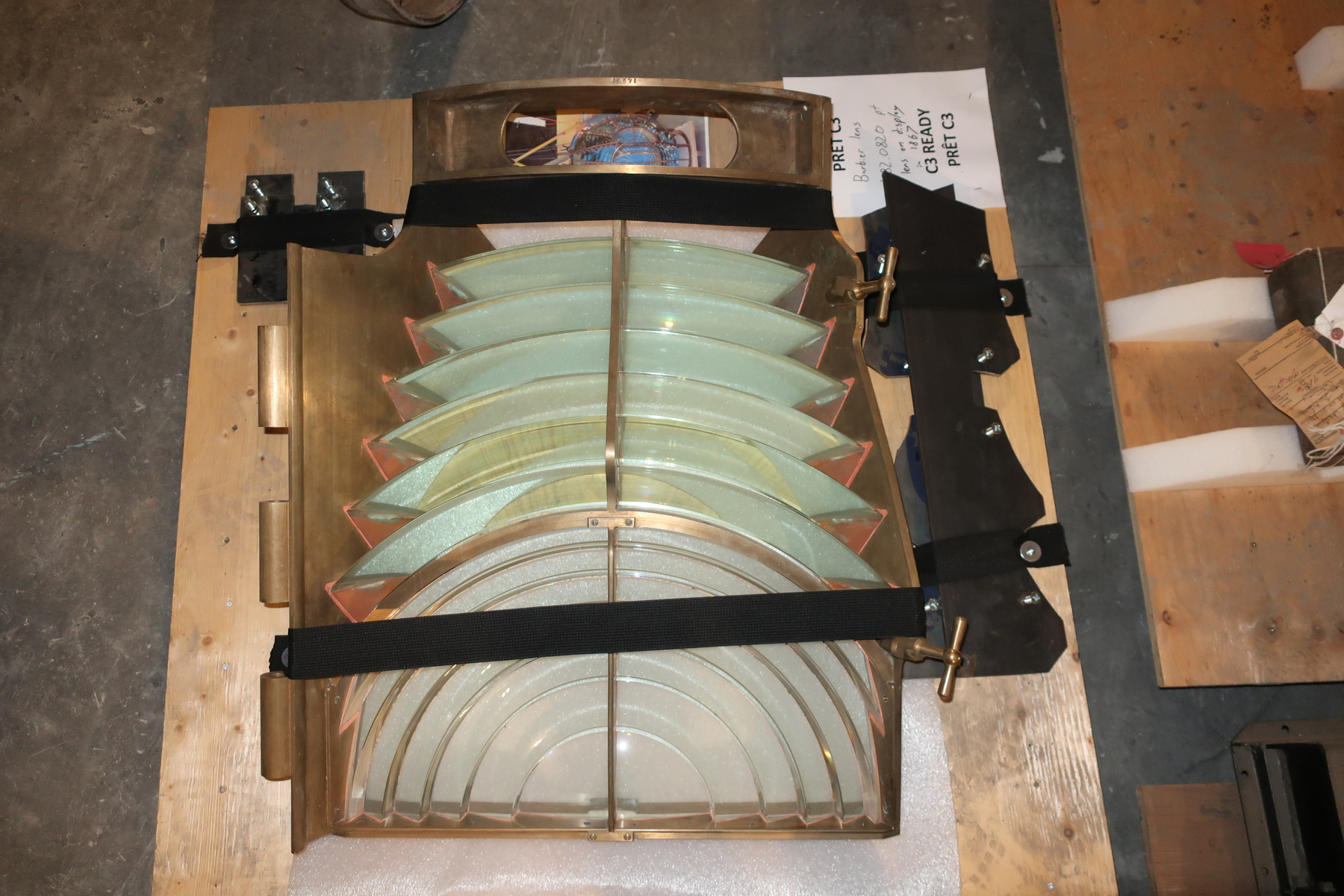

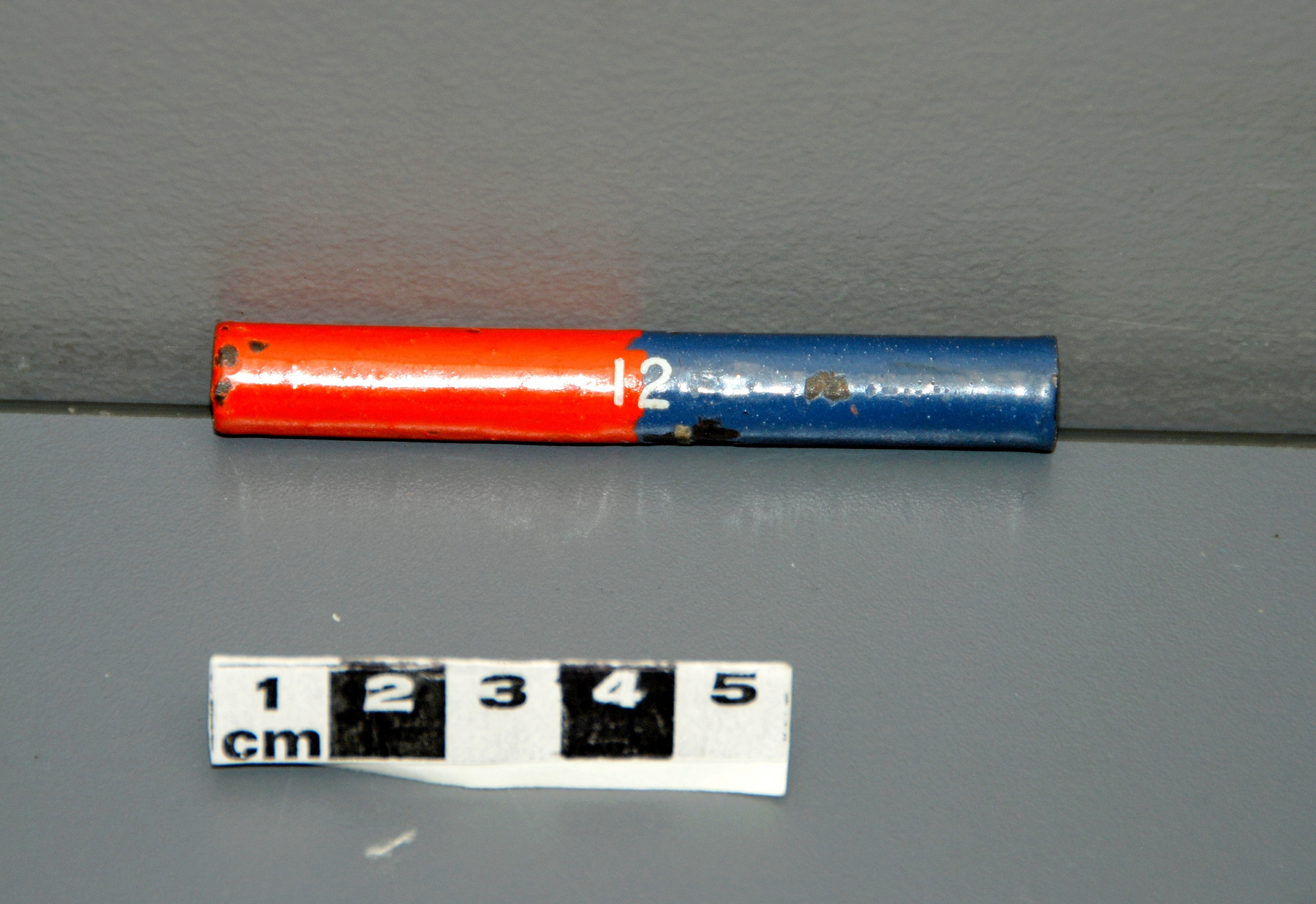

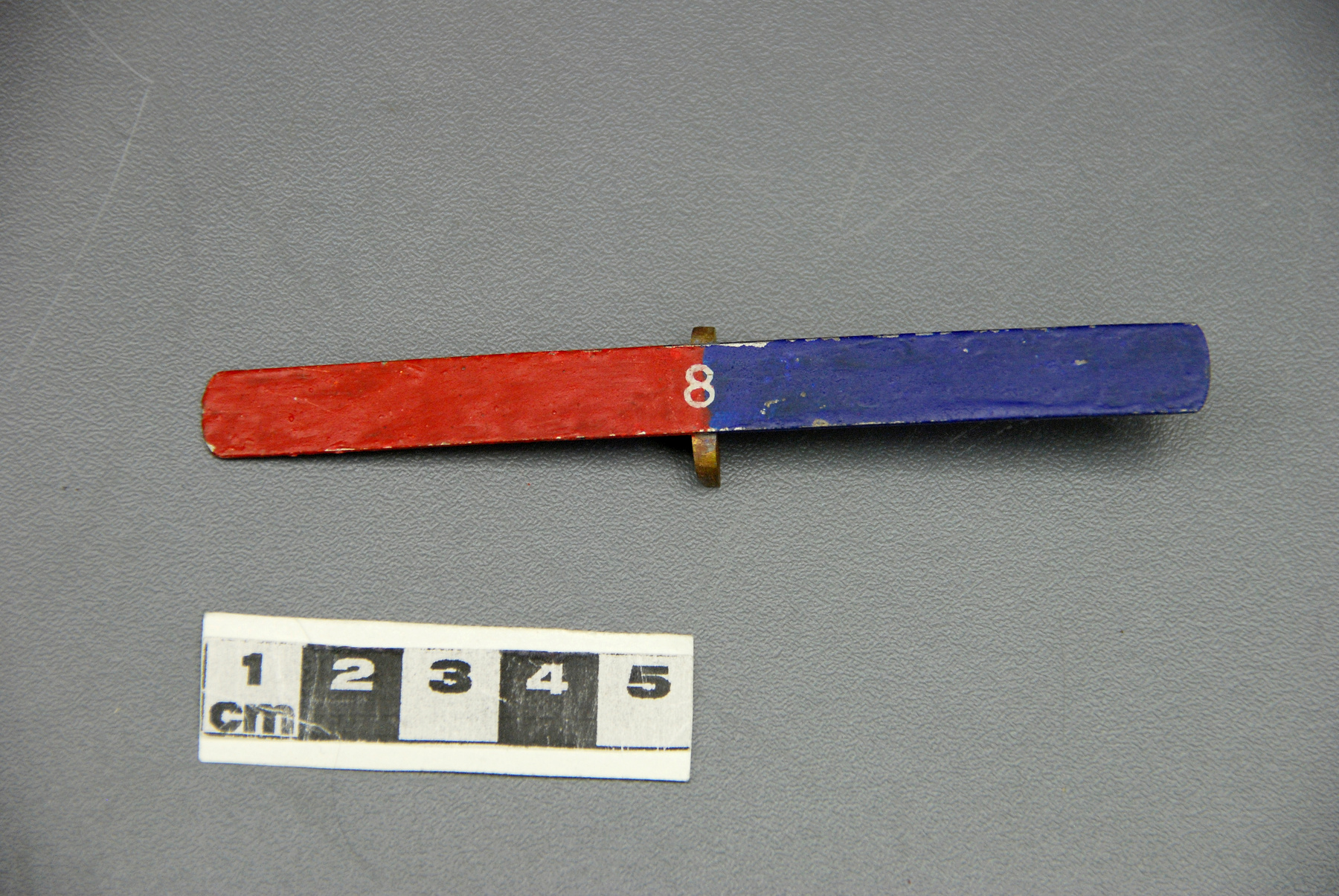

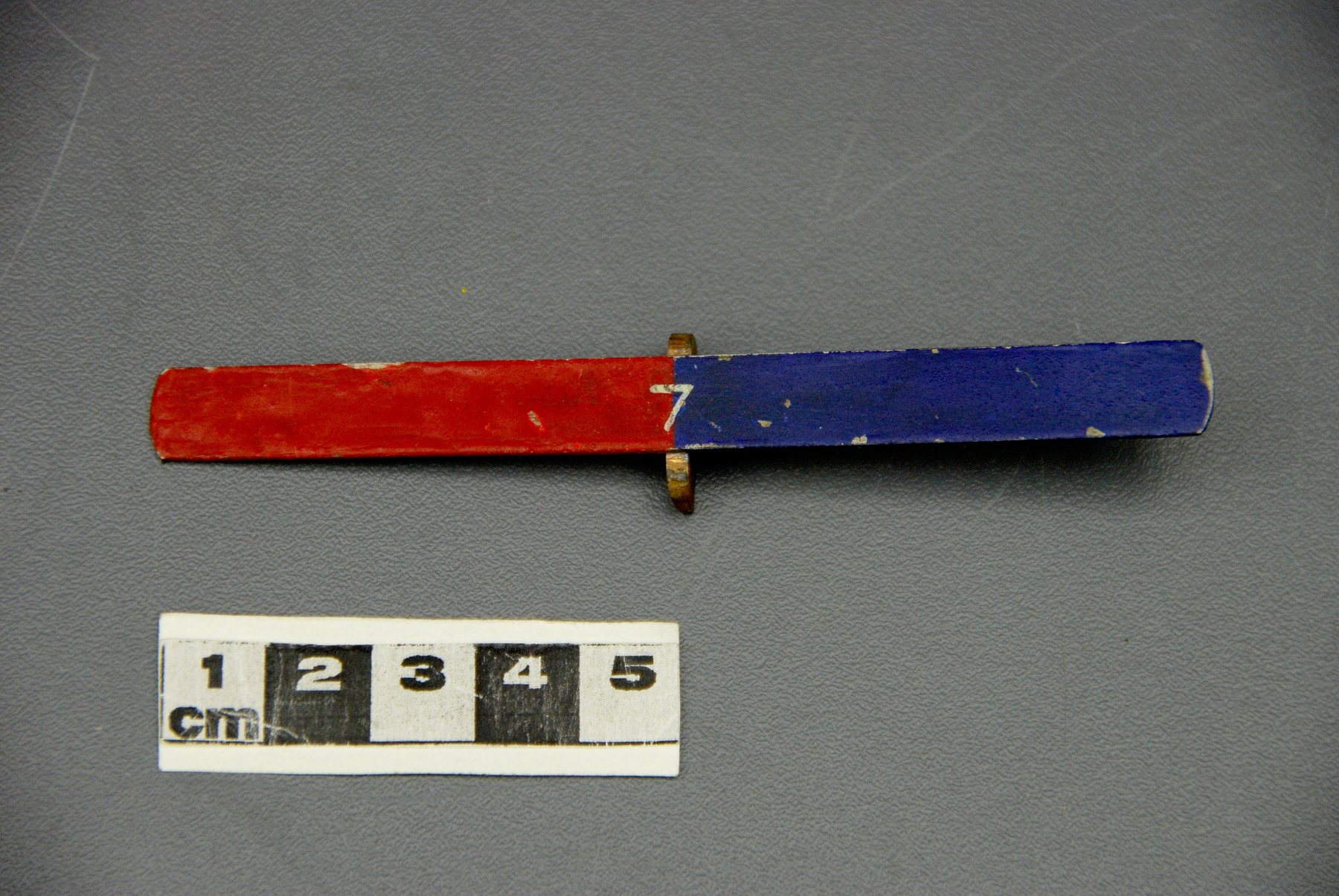

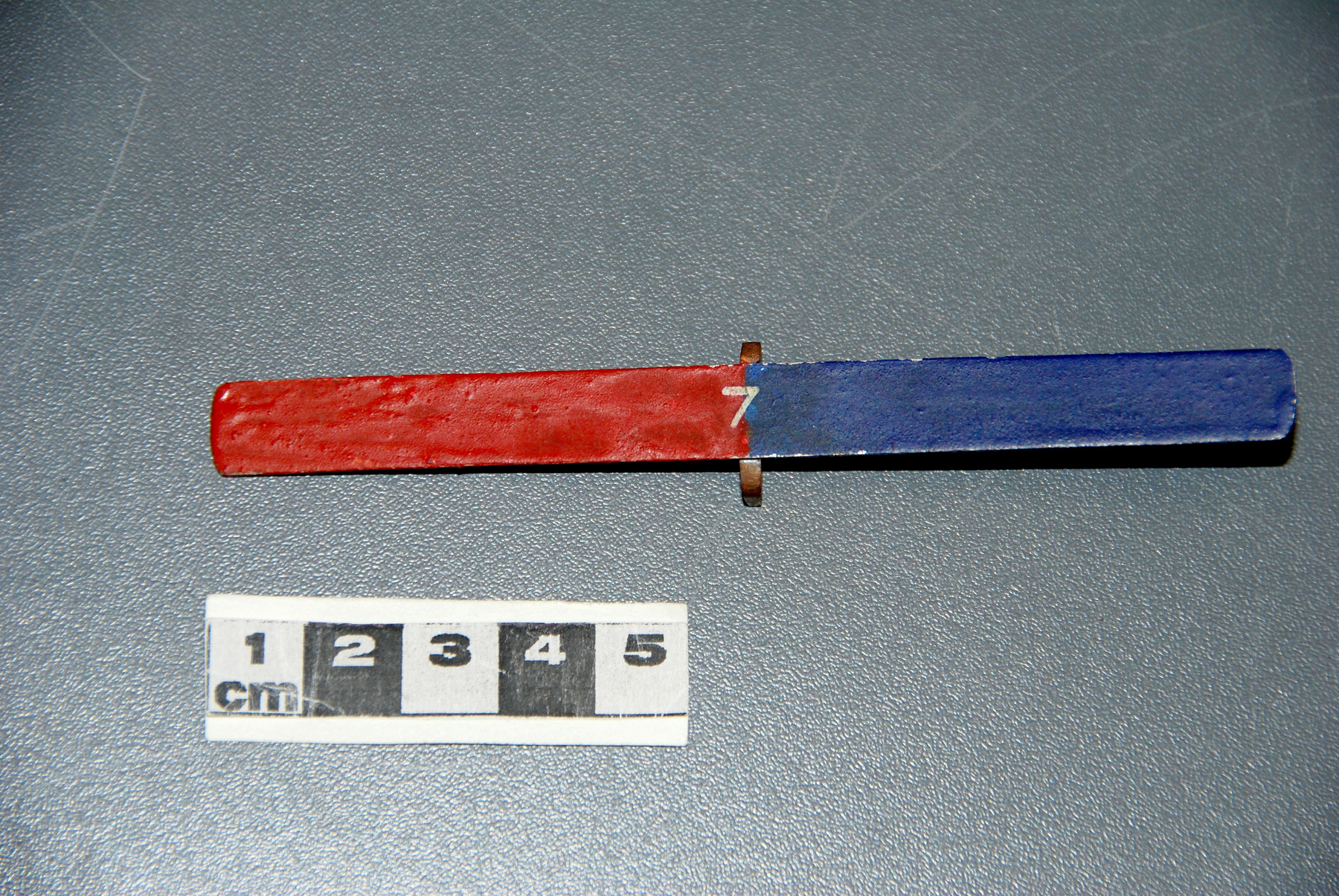

1982.0820.001

Permalien:

Ingenium diffuse cette image sous le cadre de licence Creative Commons et encourage son téléchargement et sa réutilisation à des fins non commerciales. Veuillez mentionner Ingenium et citer le numéro de l’artefact.

TÉLÉCHARGER L’IMAGEACHETER CETTE IMAGE

Cette image peut être utilisée gratuitement pour des fins non commerciales.

Pour un usage commercial, veuillez consulter nos frais de reproduction et communiquer avec nous pour acheter l’image.

- TYPE D’OBJET

- third order

- DATE

- Inconnu

- NUMÉRO DE L’ARTEFACT

- 1982.0820.001

- FABRICANT

- Barbier, Bénard & Turenne

- MODÈLE

- Inconnu

- EMPLACEMENT

- Paris, France

Plus d’information

Renseignements généraux

- Nº de série

- S/O

- Nº de partie

- 1

- Nombre total de parties

- 2

- Ou

- S/O

- Brevets

- S/O

- Description générale

- Cuprous metal frame with glass lenses and synthetic (possible) sealant

Dimensions

Remarque : Cette information reflète la taille générale pour l’entreposage et ne représente pas nécessairement les véritables dimensions de l’objet.

- Longueur

- 155,0 cm

- Largeur

- 123,0 cm

- Hauteur

- 176,0 cm

- Épaisseur

- S/O

- Poids

- S/O

- Diamètre

- S/O

- Volume

- S/O

Lexique

- Groupe

- Physique

- Catégorie

- Lumière et radiation électromagnétique

- Sous-catégorie

- S/O

Fabricant

- Ou

- Barbier

- Pays

- France

- État/province

- Inconnu

- Ville

- Paris

Contexte

- Pays

- Inconnu

- État/province

- Inconnu

- Période

- Unknown

- Canada

-

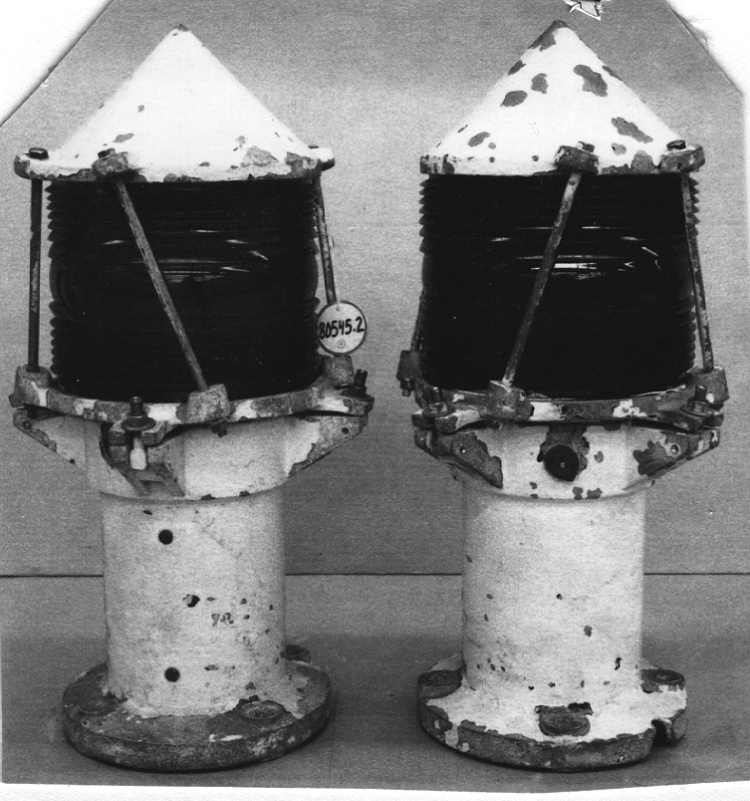

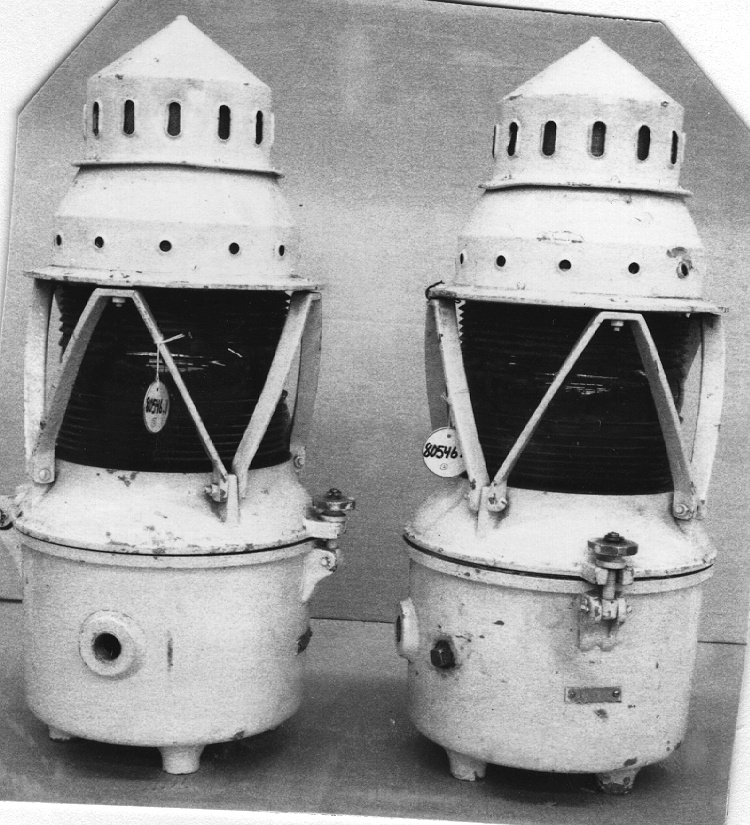

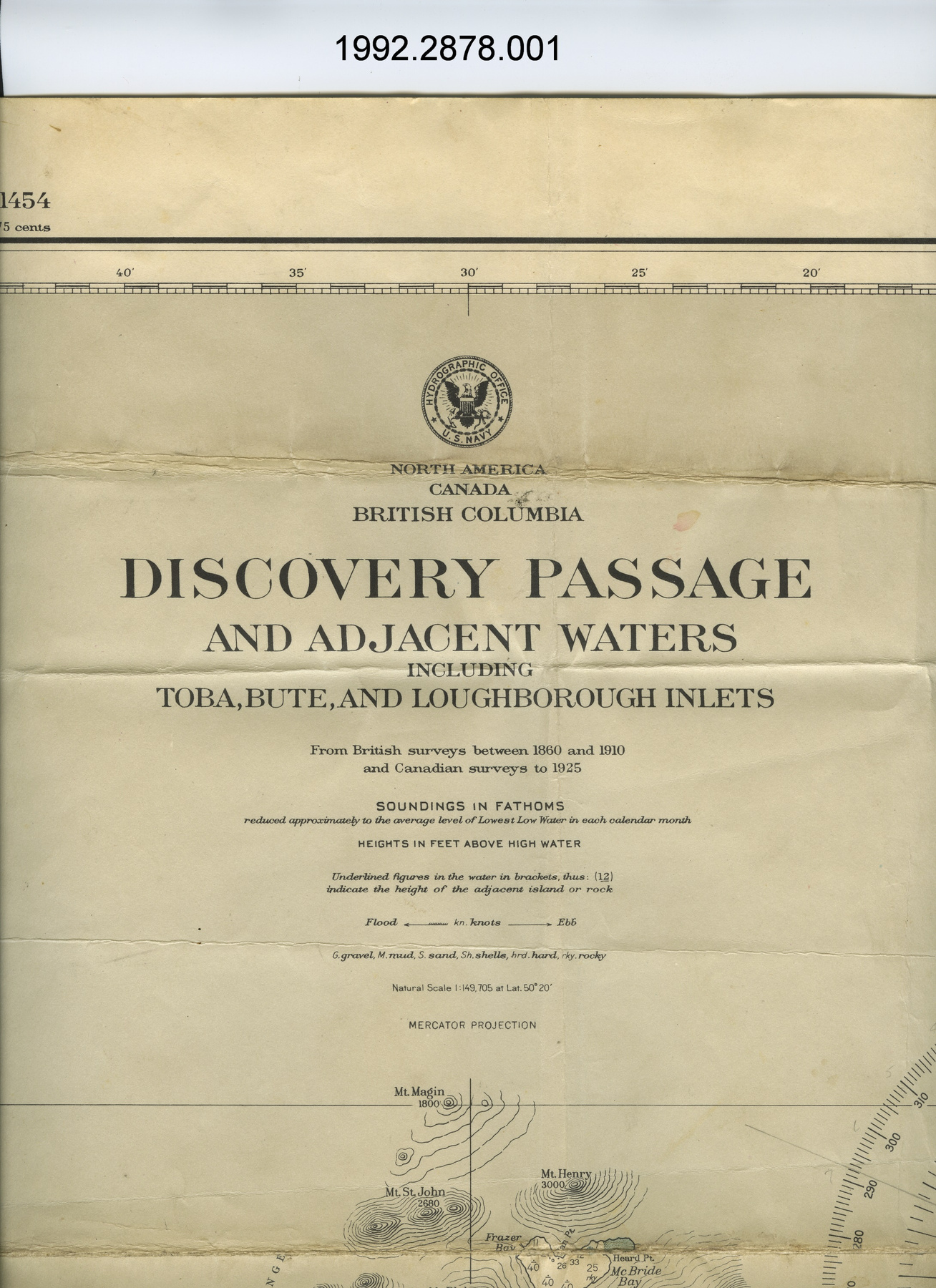

Canada has the longest coastline in the world and thousands of kilometres of navigable waterways stretching into the heart of the continent. Since European colonization, the settler communities of British North America have been very dependent on international trade for their prosperity. Much of that trade travelled by water, so establishing a network on navigational aids was of critical importance to successive colonial and national governments. Light towers, or houses, were the most elaborate, expensive, and conspicuous of these aids to navigation. Since ancient times, maritime communities and governing bodies have utilized elevated lights to help mariners establish their position and alert them to the presence of a coastline or other obstacle that might not be visible otherwise. In North America, as France and England vied for control of the continent and its riches, the safety and efficiency of shipping – naval and merchant – became a priority. Beginning in the 18th century, both colonial powers built their first lighthouses at Louisbourg in 1733 and Sambro Island in 1758. Because Canadian marine authorities had to mark many waterways and because their tax base and budget were quite meagre, they often made do with the simplest and least expense technologies. They equipped most Canadian light stations with basic catoptric or reflective lanterns. In 1872, out of a total of 314 light lighthouses, just 25 had dioptric lights. The first two were installed in 1830 on the east coast and it was not until 1858 that the colonial government invested in two first-order lights to mark the eastern edge of the continent in Newfoundland. Over the course of the late 19th and early 20th centuies, marine officials gradually converted all of the more important light stations to dioptric and catadioptric lanterns. These served their purpose well for many decades. In the years after the Second World War, the Department of Transport gradually replaced the Fresnel lenses with simpler, lighter optics that were much less costly to make and purchase and required less labour and expertise to maintain. This transition was made possible by the development of small but powerful electric light bulbs. - Fonction

-

To increase the power and visibility of lighted navigation markers like lighthouses in order to help mariners move safely along coastlines and around dangerous obstacles. - Technique

-

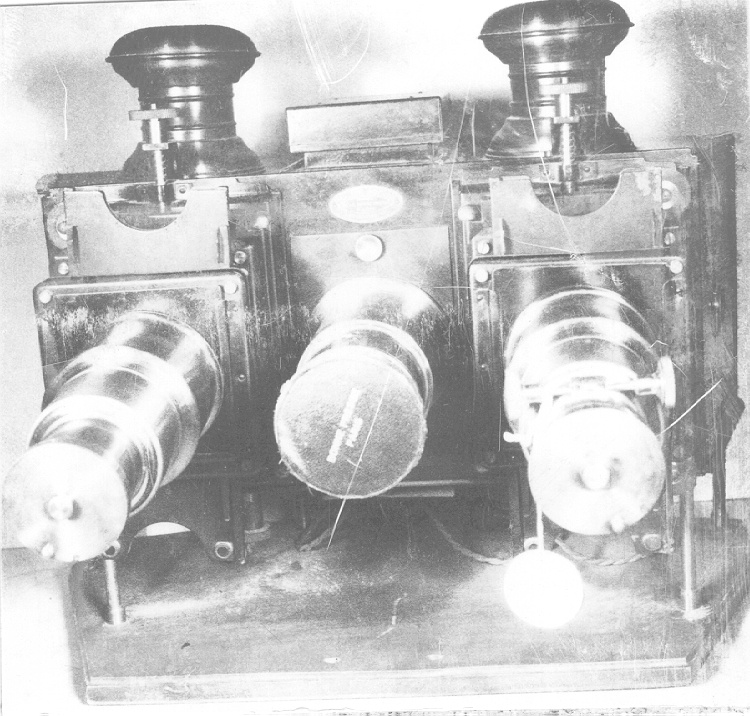

The use of lenses in lighthouses began in England in the 18th century, and was adopted in the United States by 1810. These early lenses were thick, excessively heavy, and made of poor quality glass and so were not very effective in transferring the energy from the light source out to sea. Then, in 1822, Frenchman Augustin Fresnel presented a design that used refraction to concentrate the light on the desired focal plane. By using a series of lenses and prisms, he was able to refract the light both horizontally and vertically, producing a much stronger beam of light. Installed in the Corduouan lighthouse, Fresnel’s first lens proved much more powerful than its catoptric predecessor. The manufacturing process for producing these lenses was complicated and expensive. The cutting and grinding of the lenses and prisms especially demanded a high level of skill and knowledge. As a consequence, dioptric lights were expensive. Nevertheless, given their superior performance, marine officials around the world quickly embraced this new technology and its offshoot, the catadioptric lens. The Fresnel lens could also be adapted to revolving lights, a feature that became increasingly important for safe navigation. As the number of lights marking coastlines grew through the 19th and into the 20th century, lighthouses authorities needed to find ways to distinguish one light from another. They could do this by adding colour but also by creating a distinct on/off sequence by rotating the light. Technicians had to devise mechanisms to support these heavy lenses and to keep them turning at a regular rate. The mercury float mechanism was one support system devised and it was first used in Canada in 1831 in a lighthouse on Anticosti Island. They used weight-driven clockwork mechanisms to turn the lens first wound by hand like a clock and later powered by electric motors. Lighthouses authorities around the world used Fresnel lenses well into the mid-20th century when advances in electric lighting technology made it possible to use smaller, lighter and less expensive lenses to achieve the same illumination. - Notes sur la région

-

Inconnu

Détails

- Marques

- Stamped in several places into the metal of the frame: "BARBIER, BÉNARD & TURENNE/ PARIS"/ In the corners of the frame that make up the different sections of the lens are the numbers "1," "2," "3," "4," "5," or "6" to facilitate its assembly by matching pieces together./ At the top on the proper front is a plate that reads: "19014 BARBIER, BÉNARD & TURENNE _ PARIS 14271/ Stamped into the metal at the proper bottom on the proper front: "14271"

- Manque

- Appears to be missing a piece to secure the lens access panel at the proper front.

- Fini

- Dull brass-coloured metal with clear glass and red sealant holding the glass in place with the metal.

- Décoration

- S/O

FAIRE RÉFÉRENCE À CET OBJET

Si vous souhaitez publier de l’information sur cet objet de collection, veuillez indiquer ce qui suit :

Barbier, Bénard & Turenne, Lentille de phares à signaux, Date inconnue, Numéro de l'artefact 1982.0820, Ingenium - Musées des sciences et de l'innovation du Canada, http://collections.ingeniumcanada.org/fr/id/1982.0820.001/

RÉTROACTION

Envoyer une question ou un commentaire sur cet artefact.

Plus comme ceci