Anneau

Utiliser cette image

Puis-je réutiliser cette image sans autorisation? Oui

Les images sur le portail de la collection d’Ingenium ont la licence Creative Commons suivante :

Copyright Ingenium / CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

ATTRIBUER CETTE IMAGE

Ingenium,

2010.1200.013

Permalien:

Ingenium diffuse cette image sous le cadre de licence Creative Commons et encourage son téléchargement et sa réutilisation à des fins non commerciales. Veuillez mentionner Ingenium et citer le numéro de l’artefact.

TÉLÉCHARGER L’IMAGEACHETER CETTE IMAGE

Cette image peut être utilisée gratuitement pour des fins non commerciales.

Pour un usage commercial, veuillez consulter nos frais de reproduction et communiquer avec nous pour acheter l’image.

- TYPE D’OBJET

- S/O

- DATE

- 1947

- NUMÉRO DE L’ARTEFACT

- 2010.1200.013

- FABRICANT

- Inconnu

- MODÈLE

- Inconnu

- EMPLACEMENT

- Inconnu

Plus d’information

Renseignements généraux

- Nº de série

- S/O

- Nº de partie

- 13

- Nombre total de parties

- 14

- Ou

- S/O

- Brevets

- S/O

- Description générale

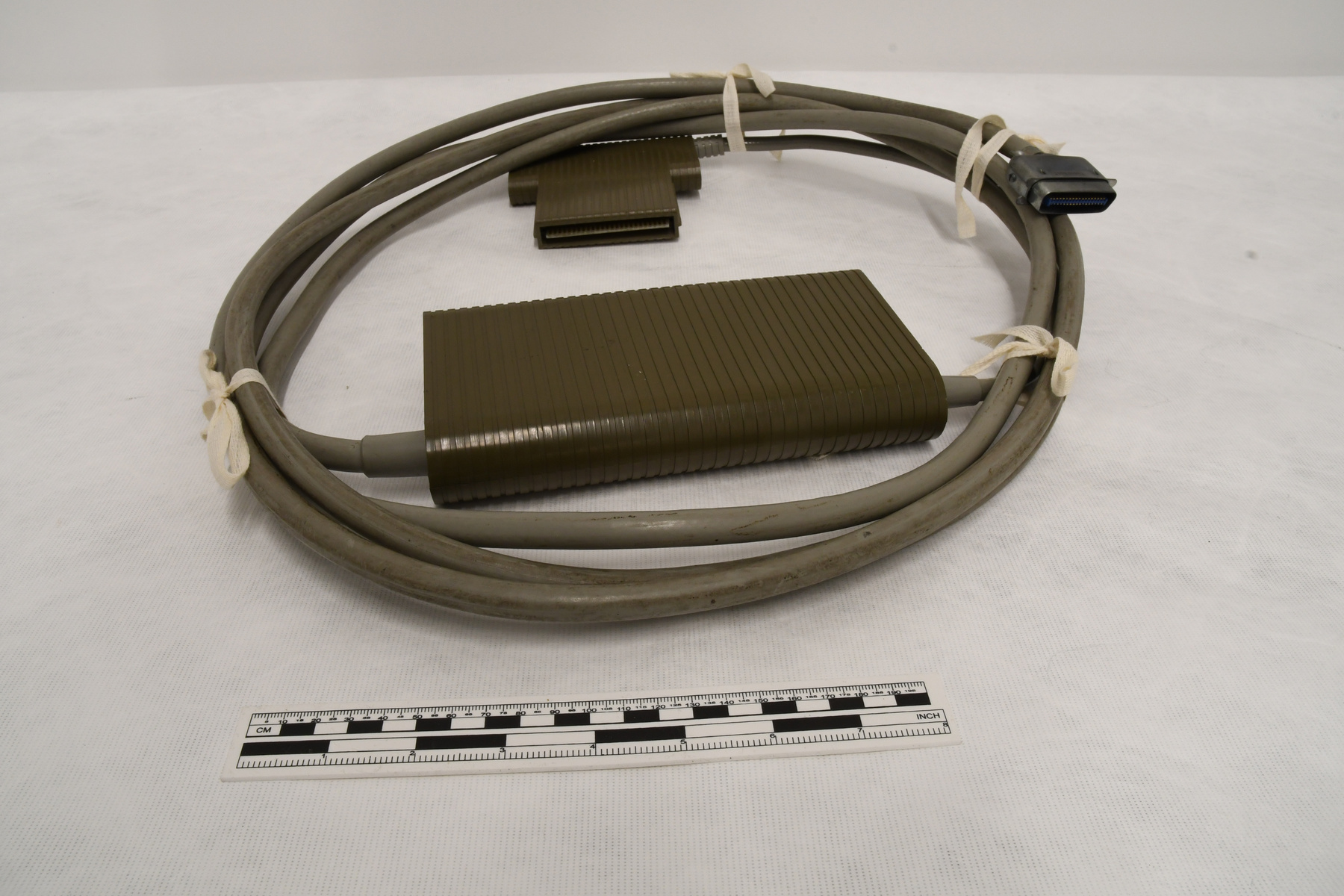

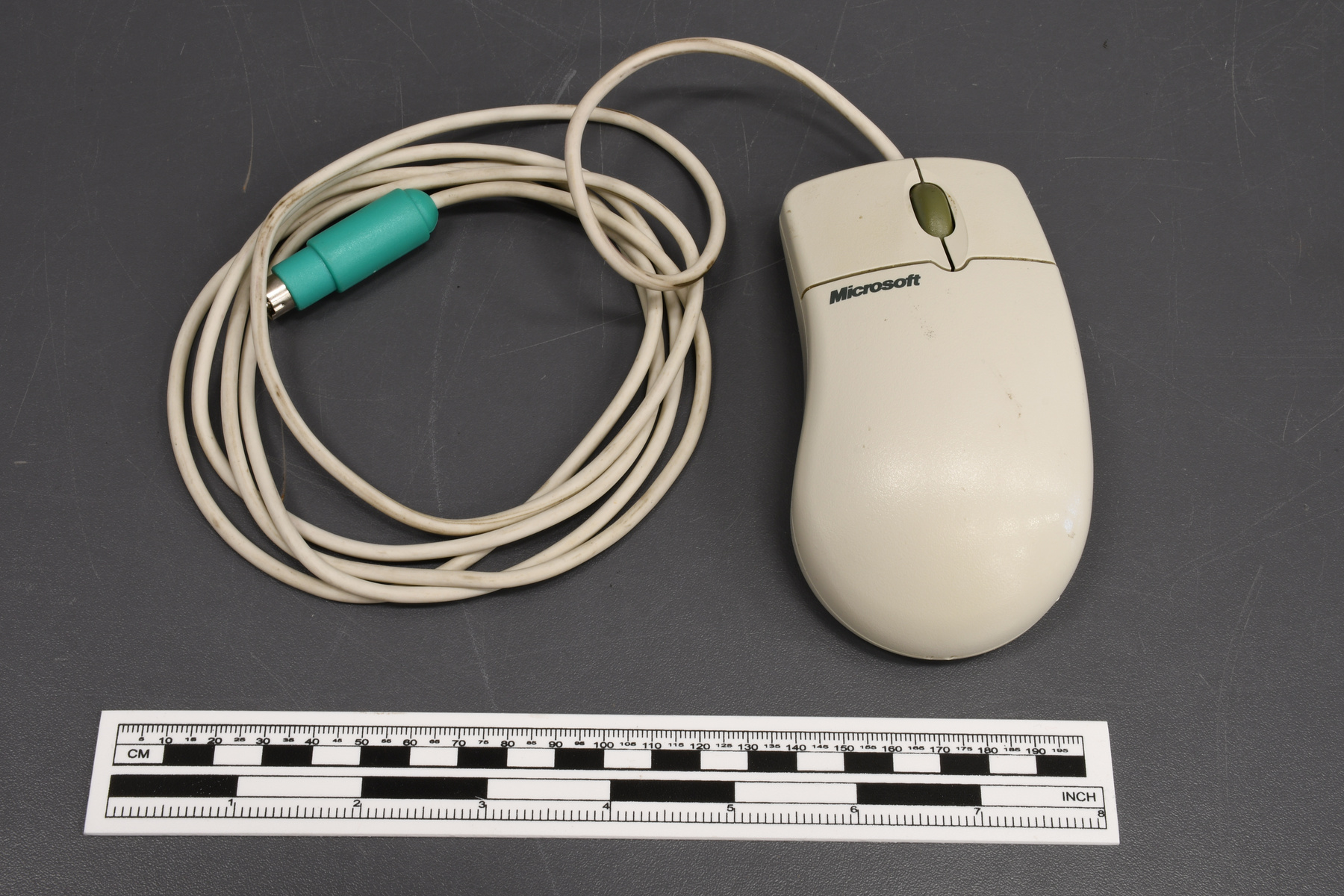

- Brass (possible) ring

Dimensions

Remarque : Cette information reflète la taille générale pour l’entreposage et ne représente pas nécessairement les véritables dimensions de l’objet.

- Longueur

- S/O

- Largeur

- S/O

- Hauteur

- S/O

- Épaisseur

- S/O

- Poids

- S/O

- Diamètre

- 2,5 cm

- Volume

- S/O

Lexique

- Groupe

- Astronomie

- Catégorie

- Équipement d'observation

- Sous-catégorie

- S/O

Fabricant

- Ou

- Inconnu

- Pays

- Inconnu

- État/province

- Inconnu

- Ville

- Inconnu

Contexte

- Pays

- Canada

- État/province

- Ontario

- Période

- 1947-

- Canada

-

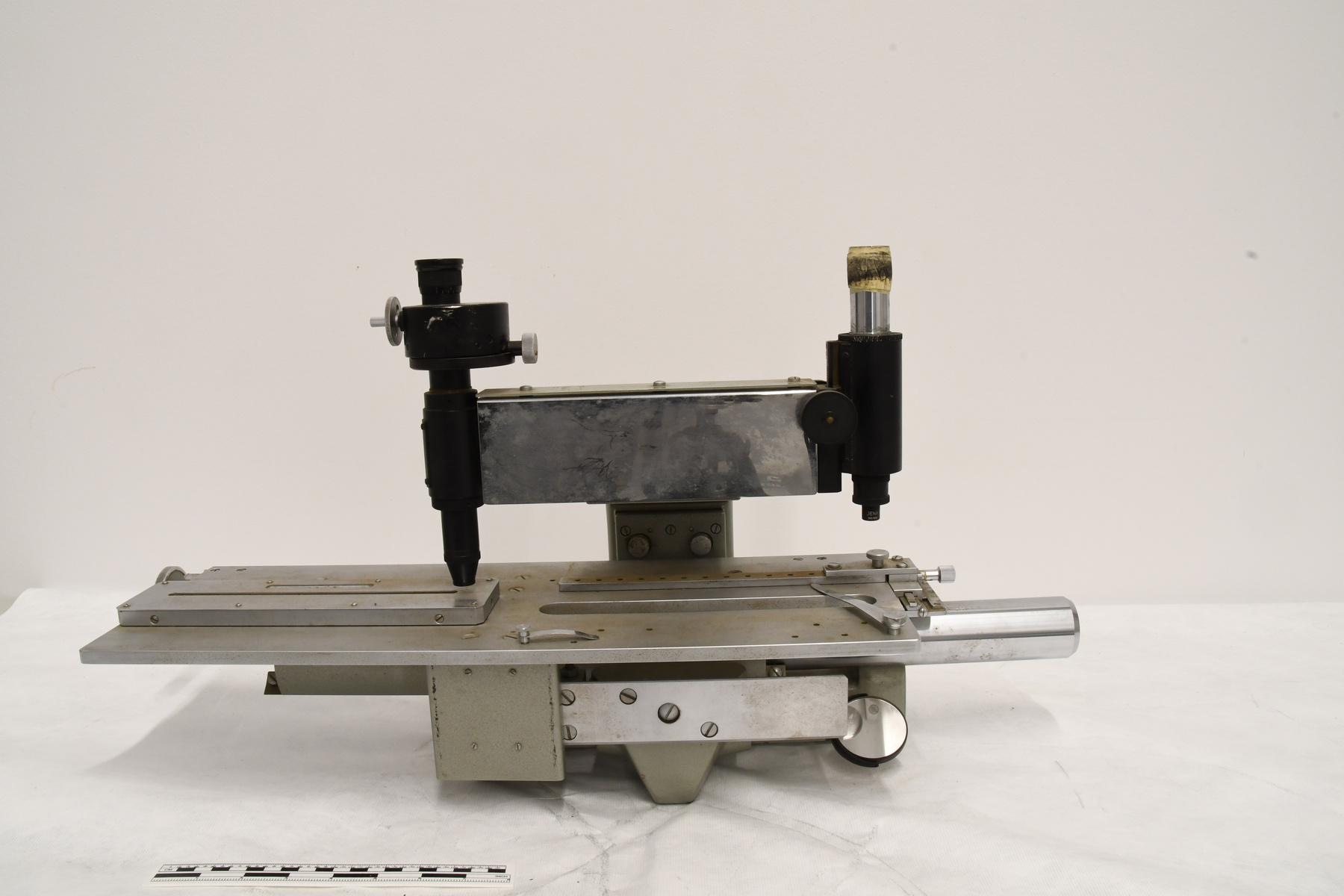

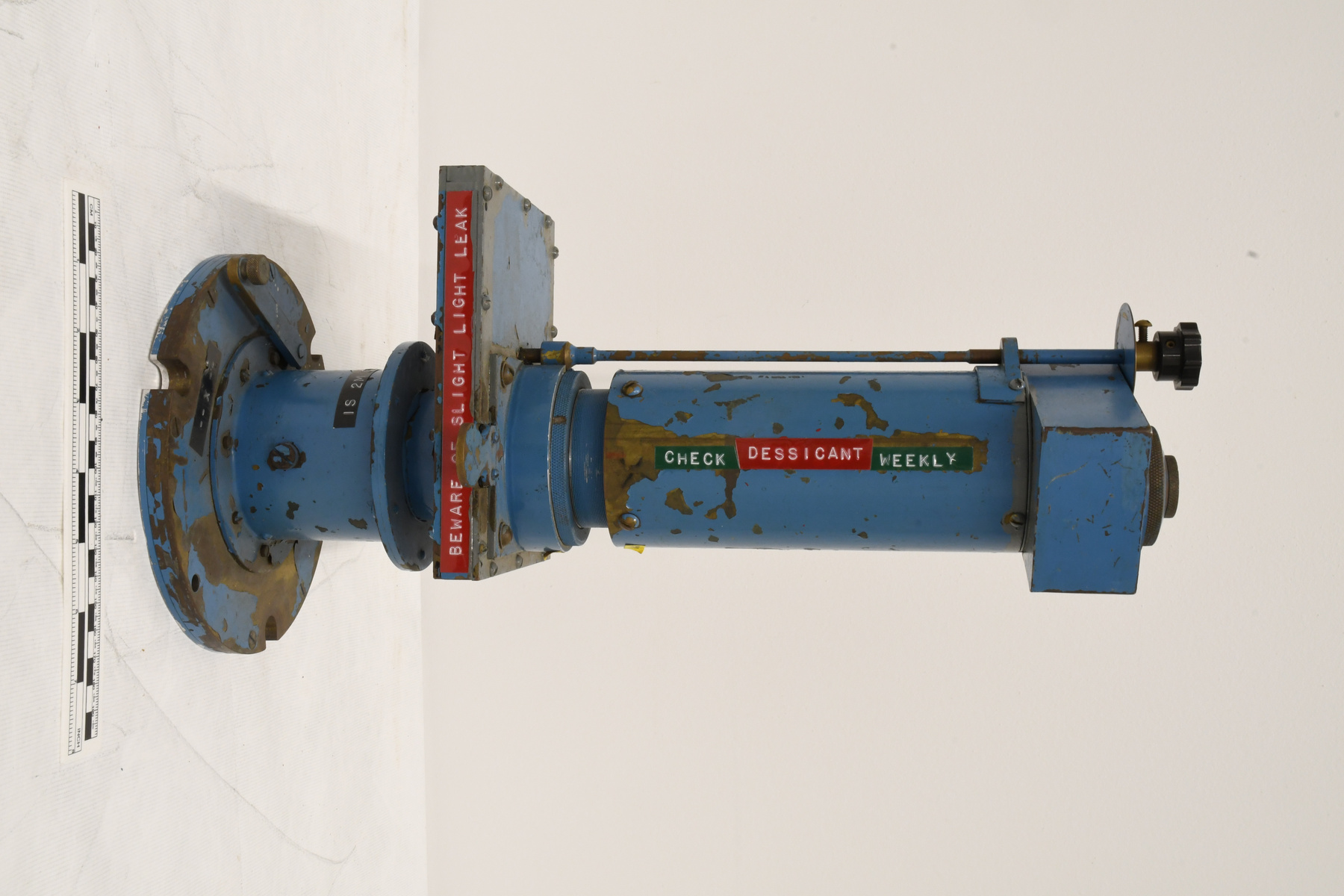

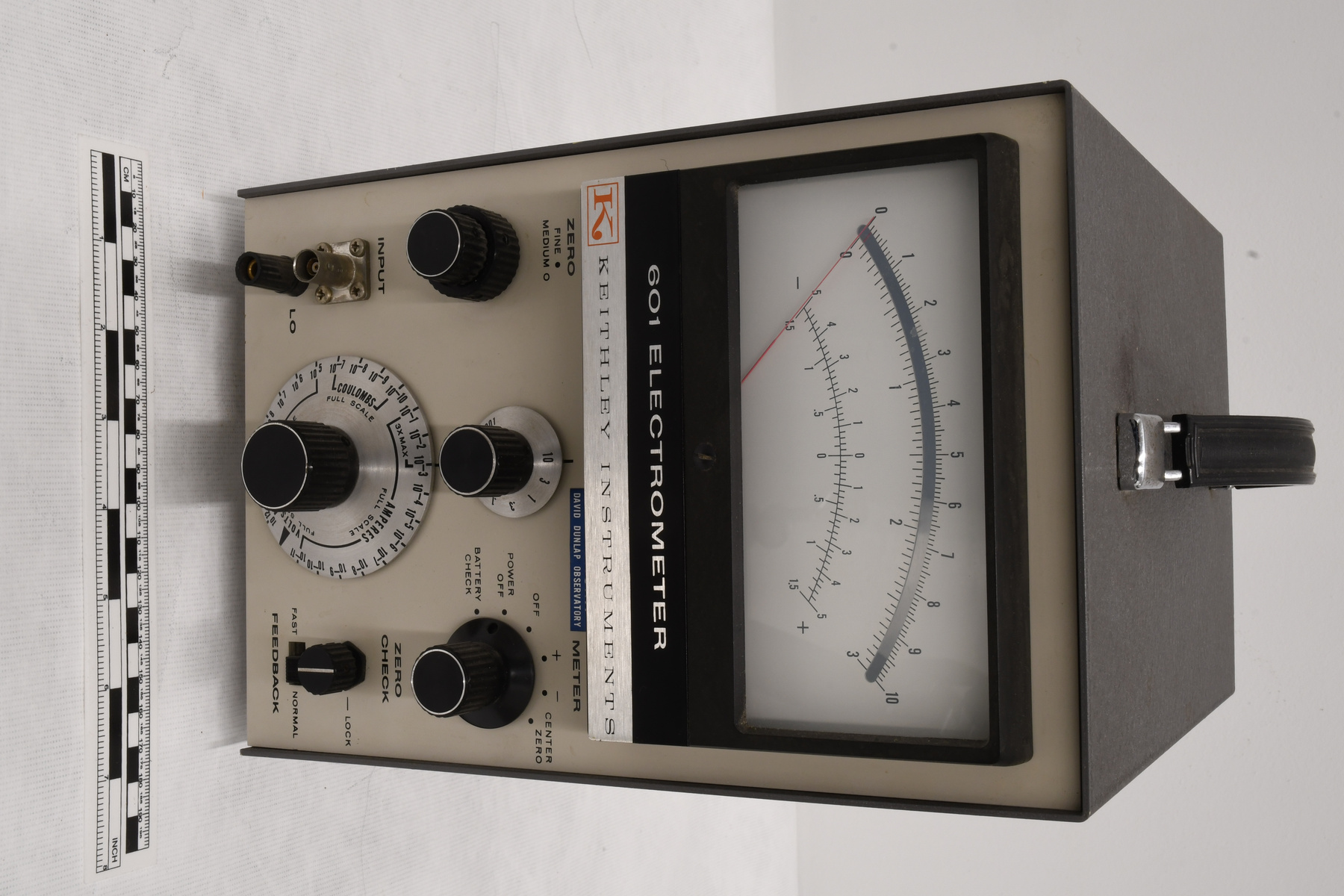

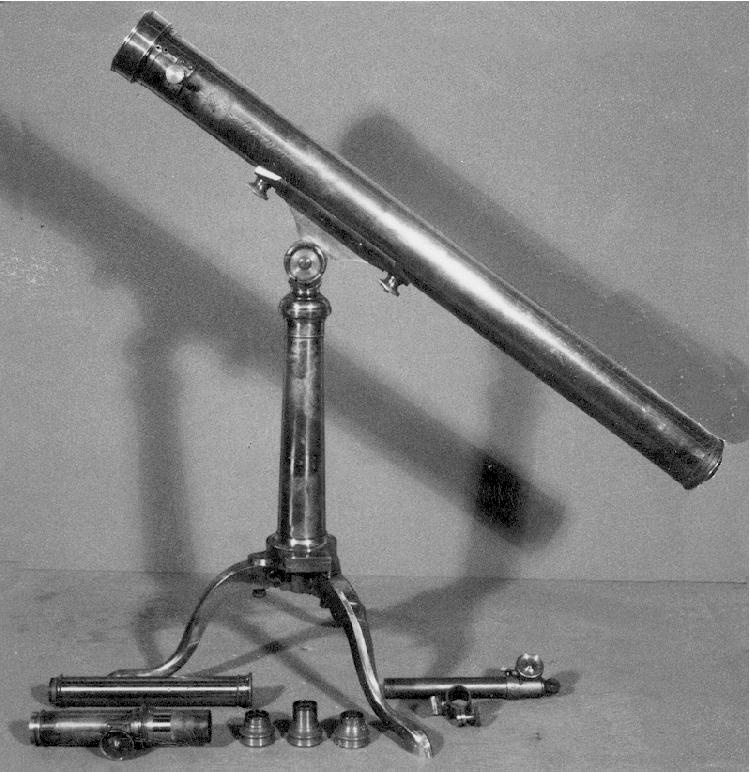

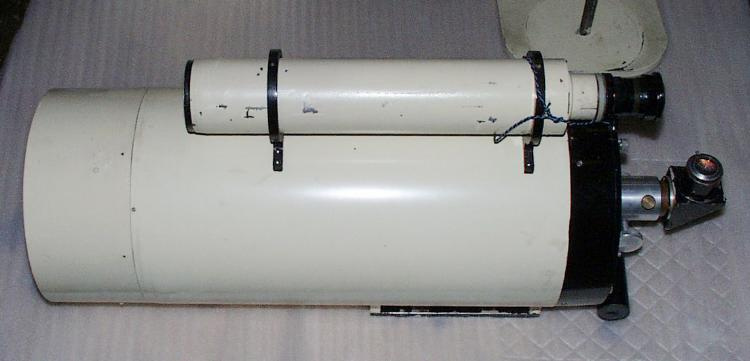

The Huschilt telescope is an excellent representation of the tradition of amateur telescope making in Canada. If we consider government astronomy, university astronomy, and amateur/popular astronomy to be the three main strands in the history of Canadian astronomy, the Huschilt telescope represents the oldest instrument available that represents the tradition of amateur astronomers building their own instruments and contributing to the public knowledge of astronomy in Canada. Huschilt used this telescope for private use, but he also taught astronomy at the University of Windsor, which makes his history more interesting. From the 1920s to late 1960s the only way many amateurs could afford a telescope was to make their own -- especially are ones with sufficient light gathering power to see faint nebulae and star clusters. One driving forces was Albert Ingalls' 3 vol. set called Ameteur Telecsope Making (copy in CSTM library). The building of the 200" at Mt Palomar may also have provided some impetus. Likewise, the competition for best amateur telescopes at Stellafane in Vt inspired many people to submit their telescopes and the best ones got lots of profile in Sky & Tel. There were also many telescopes made locally through RASC across Canada. We have not been able to collect or preserve any such telescopes. The Huschidt is a good and well-made example of a Newtonian which was what most amateurs made. Along with botany, geography, and zoology, astronomy is the science with the longest history in Canada. While astronomy was deployed early on for timekeeping and surveying, pure astronomy (observations done purely to study celestial phenomena, for private education or with a view tosharing knowledge gained thereby) go back at least to the 18th century (DesBarres at Castle Frederick). One of the earliest popular science books in Canada, Reverend Henry Hayden's Illustrations of Astronomy (1836), concerned astronomy and it turned out to be something of a bestseller (1800 copies were sold of two editions in colonial Halifax). Some of the earliest 19th-century astronomers, such as Dr Charles Smallwood in Montreal, were educated men but also amateurs, strictly speaking, though their contributions could become so important as to rival those of government or university professionals (the Smallwood observatory provided scientifically-determined time to much of Canada at one point, via telegraph and railway companies based in Montreal). Peter Broughton's Looking Up (1994) chronicles the rise of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (which goes back to 1868), though there were other associations of amateur astronomers (such as the Institut astronomique et philosophique du Canada lauched by J. Edgar Guimont in 1926, the Astronomical Association of Western Canada formed in 1909 in Winnipeg, the Société d'astronomie de Montréal, which later mutated into the Association des Groupes d'Astronomes amateurs in Québec). As can be seen in the Observer's Handbook, from the very first issue, professionals took part in the activities of the R.A.S.C., and the association served as a conduit for their knowledge to be passed on to the amateurs and, through them, to the public at large. In places like Winnipeg, their role was crucial: Broughton acknowledges that university men, including professors, held the Winnipeg Centre together in the early years, until there was a sufficient base of amateurs to keep it running. John Huschilt was such a university man involved with his local R.A.S.C. centre. However, he was not a full-time astronomer and his astronomical activities clearly qualify as an avocation. There is also a broader context. Unlike some sciences, astronomy was never completely closed to contributions from astronomers, especially in variable star astronomy. The rise of volunteer (or distributed) computing (such as MilkyWay@Home) has enrolled amateurs again, but amateur astronomers remained a fount of crucial observations throughout the 20th century. The 1987 supernova in the Great Magellanic Cloud was first observed by Canadian Ian Shelton and Chilean Oscar Duhalde with a ten-inch telescope mostly used for amateur astronomy at Las Campanas in Chile (though both were employed as assistants by the observatories on-site). Another amateur, Albert Jones in New Zealand, is credited withthe co-discovery. The Huschilt telescope is older than the Maksutov in our collection, but the latter was made by a professional optician at the Dominion Observatory. Aside from later commercial models, the other telescopes in the Museum's collection are mostly representative of government astronomy. The Museum also has equipment from the David Dunlap Observatory, but again those of from big-name makers and institutions. (From Acquisition Worksheet, see Ref. 1) - Fonction

-

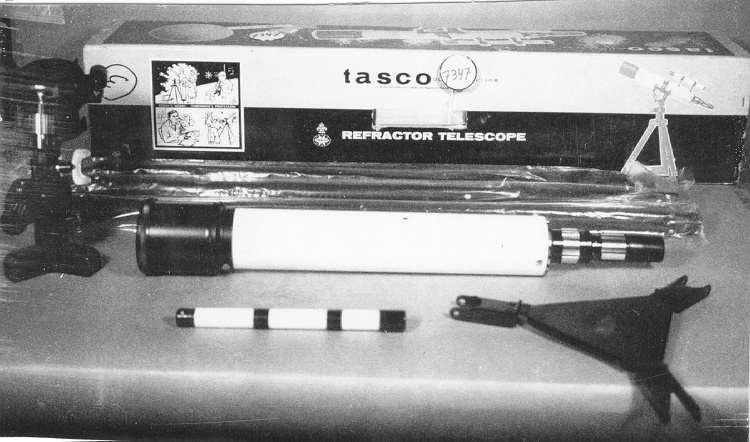

Ring is of unknown purpose. Possibly used as a spacer or connector with the telescope lenses. - Technique

-

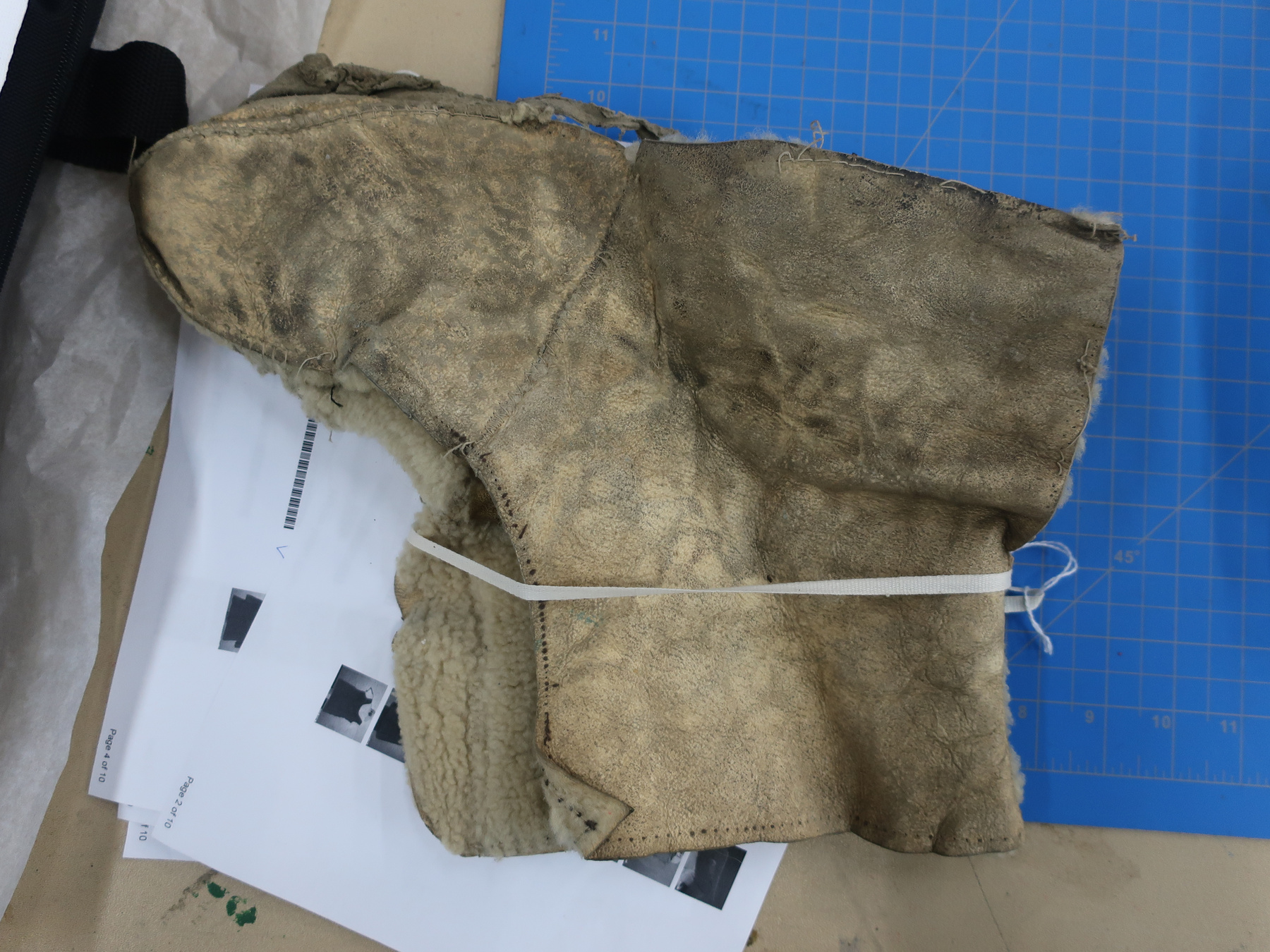

The technical significance of this telescope lies with the history behind its maker, his training and context. Ths story is best told by the maker himself: Quotes from John Huschilt 12/01/2010 08:35PM: “It may be of interest to disclose what encouraged me to build this telescope. When I was attending High School in Hamilton ON, a friend of my parents, Mr. Frank Schneider, invited me to look through a very similar telescope that he had built, at the full Moon. That was enough for me to resolve to build one as well. With his help in obtaining the necessary blank and tool, pitch, grinding and polishing materials, he guided me through the various stages, including the Foucault test to determine the shape of the mirror. He also helped in making some simple eye pieces. My father, being a tool and die worker, helped with the metal and wooden parts. After much trial and error, it was finally, successfully completed. Mr. Schneider received only a grade 6 education somewhere in Europe. He was a very active member of the RASC in Hamilton with meetings at McMaster University. He would often come to Point Pelee to observe birds in migration. Incidentally, he had lost the sight in one eye and used a monocular for these outings.” 2011/12/15 04:32 PM: “In response to your request I'm forwarding an e-mail I sent to Mr. David McCarter last December. In addition, I may add that I did keep a "log book" as the work progressed but a cursory search for it did not turn it up. My best recollection is that I worked on it ~1947-1948 in a small basement room of our modest home in Hamilton ON taking due precaution to keeping a "clean environment". Mr. Schneider provided an apparatus for the grinding and polishing of the mirror so that one could stand in one place while working on the mirror. Some assistance was also provided from articles in the magazine "Sky and Telescope". A particular feature of the telescope tube was the "brass ring" which easily permitted rotation of the eye-peice for people of different height to view or when viewing a different object in the sky. The mirror was fastened to a mount that could only be attached to the tube in one way to preserve proper alignment. The interior of the tube was blackened to diminish the effect of stray light. The telescope was used for private use, to observe the usual celestial objects, in Hamilton and in Windsor ON to where we moved to accept a teaching position at what is now the University of Windsor. I eventually taught an introductory course in Astronomy, for which the department obtained an 8-in. Celestron and 2 Questars of which I had use, and were much more easily to set up. At some point I donated the telescope to our son John who was teaching Physics in a highschool in London ON. You can say that the improvements in current amateur telescopes are astronomical. Strangely, I don't recall ever taking a photo of the telescope. I plan on checking with our son to determine if he can add anything more to this.” (From Acquisition Worksheet, see Ref. 1) - Notes sur la région

-

Inconnu

Détails

- Marques

- None apparent

- Manque

- Appears complete

- Fini

- Dull brass-coloured ring.

- Décoration

- S/O

FAIRE RÉFÉRENCE À CET OBJET

Si vous souhaitez publier de l’information sur cet objet de collection, veuillez indiquer ce qui suit :

Fabricant inconnu, Anneau, vers 1947, Numéro de l'artefact 2010.1200, Ingenium - Musées des sciences et de l'innovation du Canada, http://collections.ingeniumcanada.org/fr/id/2010.1200.013/

RÉTROACTION

Envoyer une question ou un commentaire sur cet artefact.

Plus comme ceci